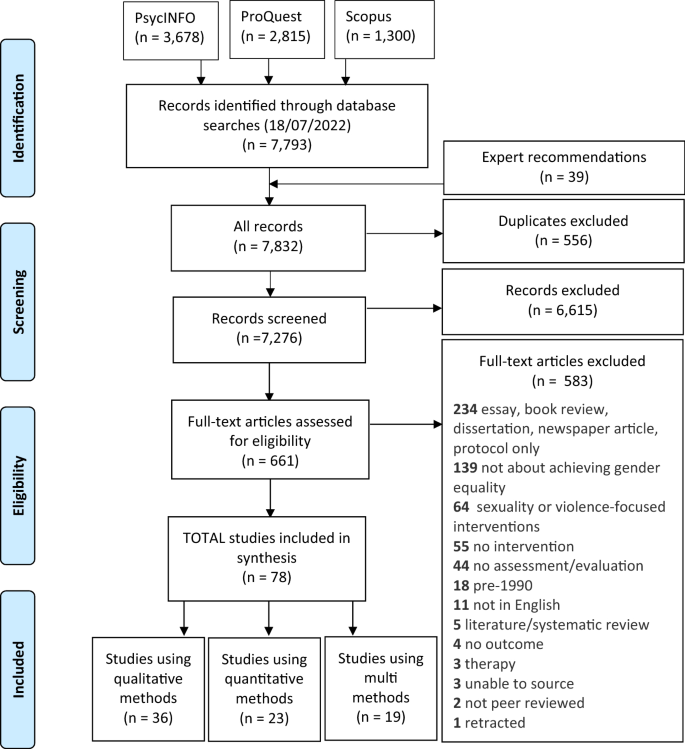

More than four decades have passed since the United Nation’s Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW) was adopted. Now is an opportune time to consider whether the interventions seeking to realise CEDAW’s aspirations have brought us closer to achieving gender equality. This systematic review aimed to identify and synthesise evidence for the effectiveness of social justice, cognitive, or behaviour-change interventions that sought to reduce gender inequality, gender bias, or discrimination against women or girls. Interventions could be implemented in any context, with any mode of delivery and duration, if they measured gender equity or discrimination outcomes, and were published in English in peer-reviewed journals. Papers on violence against women and sexuality were not eligible. Seventy-eight papers reporting qualitative (n = 36), quantitative (n = 23), and multi-methods (n = 19) research projects met the eligibility criteria after screening 7,832 citations identified from psycINFO, ProQuest, Scopus searches, reference lists and expert recommendations. Findings were synthesised narratively. Improved gender inclusion was the most frequently reported change (n = 39), particularly for education and media interventions. Fifty percent of interventions measuring social change in gender equality did not achieve beneficial effects. Most gender mainstreaming interventions had only partial beneficial effects on outcomes, calling into question their efficacy in practice. Twenty-eight interventions used education and awareness-raising strategies, which also predominantly had only partial beneficial effects. Overall research quality was low to moderate, and the key findings created doubt that interventions to date have achieved meaningful change. Interventions may not have achieved macrolevel change because they did not explicitly address meso and micro change. We conclude with a summary of the evidence for key determinants of the promotion of gender equality, including a call to address men’s emotional responses (micro) in the process of achieving gender equality (micro/meso/macrolevels).

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

The adoption of CEDAW was a remarkable achievement in the history of the women’s movement. Its ultimate aim was to catalyse social transformation that transcends cursory legislative reform (Facio & Morgan, 2009). Article 3 of CEDAW promotes this social transformation, calling for state parties to ‘take all appropriate measures’ to achieve gender equality. In practice this has included, but has not been limited to, gender-blind strategies, awareness raising, litigation, international advocacy, art and social media activism, and gender mainstreaming (see Table 1 for definition).

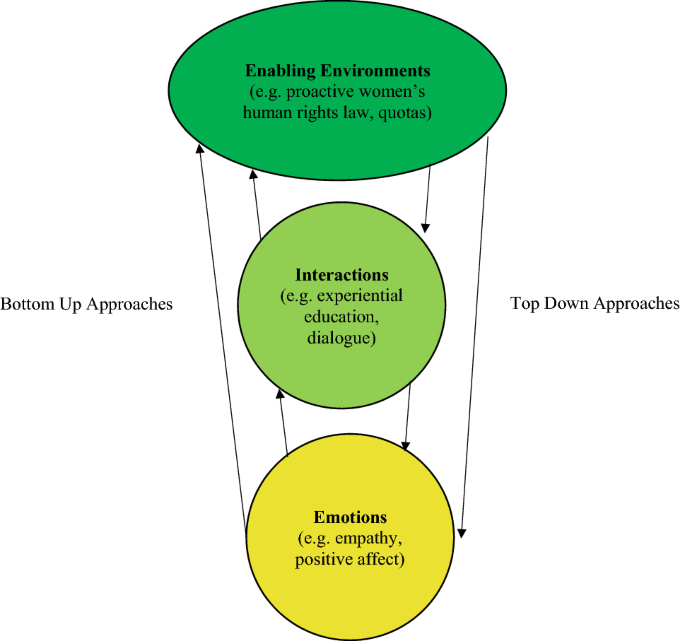

Five interventions were at the microlevel, 37 were at the mesolevel, and 17 were at the macrolevel. The final 19 interventions straddled micro-meso, meso-macro, or micro–macro. No intervention covered all three levels or took a systems thinking approach.

The overall quality of each paper is detailed in Supplementary Tables 6–8, and ratings for each quality domain are in Supplementary Tables 3–5. Studies using quantitative methods (range 0.58–1.00; median = 0.92, Q1 = 0.82, Q3 = 1.00) had significantly higher quality than qualitative (range 0.41–0.91; median = 0.73, Q1 = 0.67, Q3 = 0.79; χ2(1) = 13.71, p < 0.001) and multi-method studies (range 0.48–0.94; median = 0.76, Q1 = 0.63, Q3 = 0.82; χ2(1) = 21.96, p < 0.001). There was no difference in the quality of qualitative and multi-methods studies (p = 0.97).

All quantitative studies articulated the research question and reported the results adequately. Randomisation and blinding were used in most studies. While estimates of variance and controlling for confounding were not consistently reported, 18 studies using quantitative methods were considered to be strong quality, and seven had a perfect score.

In reports of qualitative studies, the study design, context, and conclusion were generally addressed well. However, only six studies used verification processes (see Table 1 for definition). No qualitative study received a perfect score; 20 studies were considered to be good quality.

For multi-method studies, the objective, context, data collection, analysis, and conclusion were generally reported well. Blinding was not applicable, and estimates of variance and control of confounding were generally not reported. No multi-method study received a perfect score although the quality of six of multi-methods papers was assessed as good.

Corresponding authors were contacted to confirm ethics approval; authors of two papers confirmed that the study did not receive ethics approval, and authors from 16 studies did not respond or confirm whether they had ethics approval. The omission of evidence of ethical approval is concerning and should be addressed in all future research with humans. The 18 studies with respect to which we either could not confirm ethics approval or did not receive ethics approval were all published in highly ranked journals. Furthermore, it was not, in general, clear in the majority of papers which agency or organisation conducted the intervention or undertook the study (e.g. government agency, NGO, academic researchers) making it difficult to assess reflexivity, and the prospect of future implementation.

Interventions were implemented and evaluated in various sectors: education (26 interventions); politics (10); employment (8); information, communications, and technology (6); legal (5); economics (6); health (3); sustainable development and land rights (3); sport (3); and women’s and girls’ rights (2). Interventions in the areas of conflict and of water, sanitation, and hygiene were reported in one paper each.

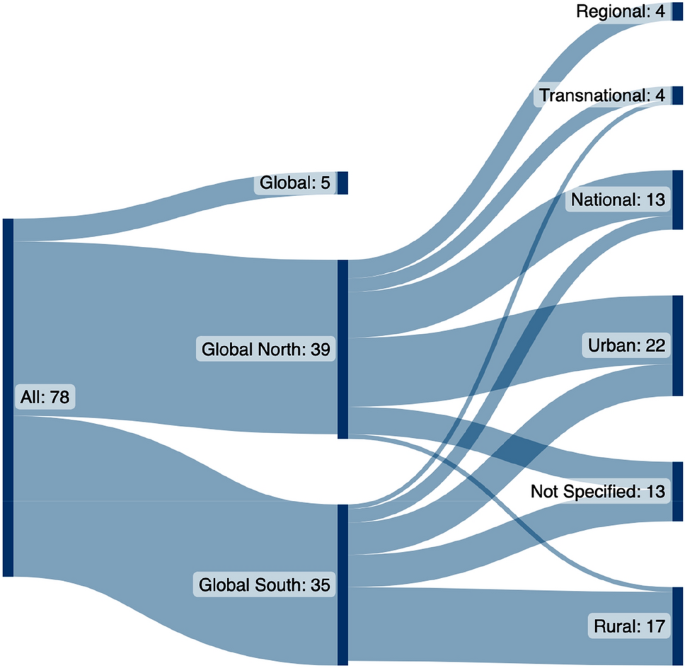

Interventions were set evenly throughout the Global South (35 papers) and the Global North (39 papers). Interventions were evaluated in Africa (15), Europe (12), North America (19), Asia (10), Latin America (6), the Middle East and North Africa (4), the United Kingdom (6), and the Pacific (4). Just under half of the Global South interventions were conducted in rural settings (16/35), whereas Global North interventions tended to be urban (22/39) (Fig. 2).

Twenty-seven interventions included both women and men as participants, 30 included only women, and one intervention included only men. Thirteen studies did not report the gender of the sample, and in seven studies gender of the sample or population was not applicable (e.g. intervention sought to affect a broad population approach irrespective of gender, such as a new law that applied to the whole population in order to improve gender equality, or a collective political party that sought to influence gender issues in parliament). Thirty papers did not report other participant demographic characteristics. Where sample characteristics were reported, participants were 10–80 years of age, with education level ranging from none to post-graduate.

All papers but one (Devasia, 1998) were published after 2005. Most papers reported data gathered across years, with twelve interventions taking place over hours or weeks. The timeframe did not appear to be associated with whether or not the intervention had a significant beneficial effect on the aims of the intervention. For example, McGregor and Davies’ (2019) two year study of the effects of a pay equity campaign achieved its aim (legislation was enacted), but Hayhurst’s (2014) girls’ entrepreneurship study that ran for several years had harmful effects (girls income was taken by men). Similarly, Zawadzki et al., (2012) board game intervention that takes 60–90 min achieved its aims but Krishnan et al. (2014) conditional cash transfer study over a month had no effect on social change.

In the qualitative and multi-method studies, theoretical frameworks were rarely reported. The few papers that did report theoretical frameworks used feminist standpoint theory, post-structuralist feminist theory, or social constructivist theory. Qualitative data collection methods were diverse: interviews (41 studies), focus groups (19), document analysis (18), observations (15), case studies (2), and visual techniques (e.g. PhotoVoice) (2). Quantitative and multi-method studies predominantly used surveys and questionnaires (22), with one study each using of the following tools: Gender Equitable Men’s Scale (Gottert et al., 2016), the Knowledge of Gender Equity Scale, the Empathy Questionnaire (Spreng et al., 2009), the Feminist Identity Scale (Rickard, 1989), and the Gender Related System Justification scale (Jost & Kay, 2003).

Few interventions aimed to achieve gender equality per se. Rather, they aimed to achieve components of gender equality (see Table 1 for definition), which ranged from gender neutrality through to striving towards a feminist revolution. Overall aims included greater awareness, inclusion, empowerment, parity, equity, and substantive equality (Supplementary Tables 6–8, column 3). The evaluation of whether interventions achieved their aims was usually assessed through surveying participants. The most common aim was to enhance “empowerment” (n = 18), which was generally not clearly defined. The interventions had various levels of effectiveness, with 37 studies having a significant beneficial effect on the aim of the intervention (i.e., they achieved their aims); 31 having a partial beneficial impact on the aim of the intervention; four studies having no beneficial or harmful impact on the aim of the intervention; and six studies having a harmful effect on the aim of the intervention (e.g., the intervention led to increased discrimination, inequality, or abuse). Examples of harmful effects include the ‘Girl Effect’ program in Uganda which resulted in participants being abused or robbed of the money they had earned (Hayhurst, 2014), and a girls’ resiliency program in the USA that resulted in increased abuse from male peers (Brinkman et al., 2011).

Evaluations of education and training interventions were reported in 18 papers (6 qualitative, 6 quantitative, 6 multi-methods). Education interventions covered a range contexts (3 micro-meso, 11 meso, 3 meso-macro, 1 macro). Most interventions (14) used awareness-raising workshops targeting individual change, and reported only partially achieving the aim of the interventions. Five workshops were assessed in randomised controlled trials. Two qualitative studies targeted increasing girls’ enrolment in formal education in Morocco (Eger et al., 2018) and India (Jain & Singh, 2017), both of which achieved the aims of the interventions. One qualitative study in the Democratic Republic of Congo targeted behaviour change in men only (Pierotti et al., 2018), which had a partial beneficial effect because men increased their willingness to contribute to household chores but maintained control over the broader gender system. This intervention was an eight-week long mesolevel men’s discussion group focused on “undoing gender” through social interaction (e.g. promoting a more equal division of labour in the household, improving intra-household relationship quality, and questioning existing gender norms).

Gender parity in schools did not signal an end to, or transformation of, gender inequities in the schools or communities studied (Ralfe, 2009). To bring about education policy reform, Palmén et al. (2020) found that top-down institutional commitment to gender equality was essential to create change. However, bottom-up strategies were also needed as teachers had to foster cooperative learning that encouraged working together and valuing different abilities across genders (Sánchez-Hernández et al., 2018). Sufficient resources, in addition to monitoring and evaluation of education initiatives, were found to be a key to intervention success (Palmén et al., 2020). Ultimately, social norms did not change beyond the school environment (Chisamya et al., 2012; Jain & Singh, 2017).

While interventions in traditional education contexts only partially achieved their aims, experiential learning was found to be a powerful process to deliver knowledge about gender equity in a nonthreatening way (Zawadzki et al., 2012a). Zawadzki’s study was a mesolevel intervention that used a board game to teach participants the cumulative effect of subtle, nonconscious bias, to discuss how bias hinders women’s promotion in the workplace, and to find solutions for what can be done to reduce that bias. They found that the delivery of information was less effective when new knowledge did not promote self-efficacy or lead participants to resist perceived attempts to influence their beliefs or behaviours. Furthermore, they established that learning about gender inequity was not sufficient for knowledge retention. Rather, participants had to link the knowledge to their own experiences and be empowered to feel that they could act on that knowledge.

Awareness-raising interventions in education and training generally only partially achieved the aims of the interventions, and did not necessarily translate into behaviour change (Ralfe, 2009). In the strong quality (0.93) quantitative mesolevel study by Moss-Racusin et al. (2018), the Video Interventions for Diversity in STEM (VIDS) intervention was found to achieve significantly greater awareness of bias in participants compared to the non-intervention control condition; however, effects on behaviour were not assessed. This intervention presented participants with short videos about findings from gender bias research in one of three conditions. One condition illustrated findings using narratives (compelling stories), the second presented the same results using expert interviews (straightforward facts), and a hybrid condition included both narrative and expert interview videos.

A lack of awareness, knowledge, or understanding of women’s human rights was found to be a key barrier to the achievement of gender equality in education-based interventions (Murphy-Graham, 2009). Gervais (2010) reported that awareness-raising can have direct effects on participants by giving them confidence to speak up against violations of their rights, although they noted that this might anger violators. Similarly, education was found in some cases to enable women to negotiate power-sharing with their husbands, while other women were verbally abused and threatened because their husbands disapproved of the education program (Murphy-Graham, 2009). Similar to the study by Pierotti et al. (2018), Murphy-Graham (2009) sought to “undo gender” by encouraging students to rethink gender relations in their everyday lives (mesolevel). Including men together with women in education programs enabled women to gauge men’s reactions to social change in a safe environment (Cislaghi et al., 2019). Potential harmful effects of interventions are further summarised under the ‘The problem of hostile affect’ header below.

Among education interventions were a subset of Science, Technology, Engineering and Maths (STEM) education interventions. These specifically targeted secondary school girls as a pathway to tertiary STEM education, and were reported in eight papers (1 qualitative, 3 quantitative, 4 multi methods). The design of interventions varied from science clubs, outreach programs, after school sessions, residential camps and immersion days. Archer et al. (2014), however, took a multipronged approach. Their intervention included school excursions, visits from STEM Ambassadors and a researcher-in-residence, a STEM ‘speed networking’ event, and participation in a series of teacher-led sessions for girls aged 13–14 years. Despite this significant investment, the intervention did not significantly change students’ aspirations of studying science, although it did appear to have a beneficial effect on broadening students’ understanding of the range of science jobs.

All STEM education interventions were aimed at the mesolevel and were located in the urban Global North. While the long-term impact (e.g. increased enrolment of women into tertiary STEM education) were inconsistent among studies. Gorbacheva et al. (2014) found that secondary same-sex education had no influence on this objective. Alternatively, Hughes et al. (2013) found having role models was more critical than sex segregation. Finally, Lackey et al. (2007), Lang et al. (2015) and Watermeyer (2012) all established that a network of support (e.g. family, school, industry) made a positive difference to girls equality in STEM education.

Eight interventions focused on women’s employment: 4 qualitative, 2 quantitative, 2 multi-methods studies. They covered a range of contexts (1 micro/meso, 5 meso, 2 meso/macro). Three interventions addressed women’s promotion (Eriksson‐Zetterquist & Styhre, 2008; Grada et al., 2015; Smith et al., 2015). Two interventions evaluated microenterprise; one produced harmful effects (Hayhurst, 2014), and the other only partially achieved its aim (Strier, 2010). Hayhurst (2014) evaluated an intervention auspiced by the Nike Foundation and concluded that it had an unfair and deleterious effect by placing the burden of social change on girls. In this intervention, focusing on the mesolevel, girls were taught to be entrepreneurs to enable them to escape abuse, buy land, grow food, and work. In practice, this economic empowerment strategy led to increased abuse by men who wanted to take the girls’ money to pay their own taxes and fines. This study was good quality (0.73). Participants in the study by Strier (2010) thought that microenterprise promised self-realisation and escape from the slavery of the labour market, but they found it to be a false promise, characterising the informal sector as both a disappointment and a fraud. Overall, employment interventions led to unreliable and inconsistent outcomes.

Six interventions (1 qualitative, 2 quantitative, 3 multi-methods studies) addressed various contexts (1 micro, 1 micro/macro, 2 meso/macro, 2 macro interventions) that targeted economic empowerment. Overall, the interventions partially achieved their aims. For microfinance interventions, women benefited less than men because they were given smaller loans for less lucrative businesses (Haase, 2012). Krishnan et al. (2014) conducted a good quality (0.79) multi-method study of a micro–macro level intervention that provided conditional cash transfers in India, and found minimal positive effects from the implementation of this scheme to address social behaviours related to valuing girls. In this study, parents had to register the birth of their daughter in order to receive financial benefit, but this did not transform the social mindset that daughters are a burden. In another study, the size and frequency of cash transfers directly influenced outcomes: large but infrequent payments enabled investment that could facilitate economic transformation (Morton, 2019). Lump-sum payments also challenged stereotypes about what women could invest in, and could transform the gender asset gap. Institution of a social protection floor (e.g. welfare benefits) enhanced women’s power and control over household decision-making in financial matters and household spending in South Africa (Patel et al., 2013). While a social protection floor had benefits for women’s empowerment at the microlevel, it did not transform unequal and unjust gendered social relations of power at the macrolevel.

Five interventions (3 qualitative, 2 quantitative studies) in two contexts (1 meso/macro, 4 macro) reported on legal interventions. In Zartaloudis’s (2015) qualitative macrolevel study of an employment strategy in Greece and Portugal, legislation was found to have an important but not transformative effect on gender equality in employment. Three other studies found that changes in law must be accompanied by incentives and penalties in order to be effective (Kim & Kang, 2016; Palmén et al., 2020; Singh & Peng, 2010). While the decline in levels of discrimination was at first sharp after enacting anti-discrimination legislation, its implementation plateaued over time, calling into question the long-term sustainable effects of law reform without adequate enforcement mechanisms. In this macrolevel study by Singh and Peng (2010), the Ontario Pay Equity Act was effective because it was proactive in persuing pay equity, rather than being complaint based.

Legal opportunity and litigation were strategic choices in campaign strategies in one study, playing an important role in effecting change to prevent discriminatory pay for work typically performed by women (McGregor & Davies, 2019). The strong quality (0.92) macrolevel study by Mueller et al. (2019) increased access to legal services in order to improve legal knowledge in rural Tanzania. It found that, despite increased access to legal services, women still had moderate to low knowledge of marital laws, and only 2.7 percent of women would refer someone to a paralegal for problems with a widow’s assets, divorce, or marital disputes. Mueller et al. (2019) concluded that an increased investment in access to justice needed to be made through informal channels (mesolevel change) in addition to the macrolevel law reform.

Ten papers (4 qualitative, 3 quantitative, 3 multi-methods studies) that covered a variety of contexts (1 micro/meso, 2 meso, 2 meso/macro, 5 macro) reported assessments of political interventions. Electing women to council increased other women’s access to councillors because women had greater heterosocial networks (i.e., comprising women and men), but did not affect men’s access to councillors (Benstead, 2019; Levy & Sakaiya, 2020). However, increasing the number of women in public office did not necessarily improve equality (McLean & Maalsen, 2017). For example, an evaluation of gendered outcomes of Hon. Julia Gillard’s tenure as Prime Minister of Australia saw increased gender-based denigration and vilification of her leadership (McLean & Maalsen, 2017).

A qualitative macro study using interviews and ethnography to explore the impact of political gender quotas in Mali (Johnson, 2019) found that savings groups, together with political gender quotas, were important for catalysing the first steps towards social and political transformation. In Mali, gender quota laws required political parties to field a minimum of 30 percent women candidates, and to include a woman within the first three places on a party’s candidate list. In this context, savings and credit associations developed women’s self-efficacy and increased their confidence to become political candidates (Johnson, 2019).

An example of discursive change based on political activism was found by Cowell-Meyers’ (2017) multi-method study examining the impact of a new feminist political party in Sweden. Near consensus by political parties that gender equality needed to be tackled through government intervention was achieved through the efforts of the small women’s rights party. However, another multi-method mesolevel study examining the effects of Transnational Advocacy Networks (TANs) in Europe found that they either ignored or subverted gender mainstreaming language (S. Lang, 2009). Gender mainstreaming policy interventions were found to have only partially achieved their aims, but were successful when law and policy detailed specific roles and responsibilities for action (Kim & Kang, 2016). Policymakers in two other studies were found to avoid the responsibility of implementation not because they opposed gender mainstreaming itself, but because they objected to being forced into it (Hwang & Wu, 2019; Kim & Kang, 2016). Therefore, the attitude of bureaucrats (microlevel) was considered to be an important factor in implementing gender equality initiatives at the macrolevel.

The strong (perfect quality score) quantitative study by Saguy and Szekeres (2018) reported on the effect on gender-based attitudes (microlevel) following exposure to the 2017 Women’s March across the US and worldwide in response to Donald Trump’s inauguration. The research found that large-scale collective action had a polarising effect on those exposed to it. Over time, men who identified more closely with their own gender increased the degree to which they justified gender inequality after exposure to the protests, suggesting a backlash reaction (mesolevel). People who were found to be positively affected by collective action were already in favour of the protesters’ cause. The backlash found for high-identifying men was explained by reactance theory (Brehm, 1966) whereby people become motivationally aroused by a threat to or elimination of a behavioral freedom (Brehm, 1989).

No study accounted for men’s and boys’ emotions (microlevel change) as part of the aim and design of the intervention, but their significance became apparent in the results of several studies. Men and boys reported feeling hostility, resentment, fear and jealousy when social norms were challenged. Attempts at addressing gender inequality were found to threaten men’s sense of entitlement, and it was theorised that boys expected to be the centre of attention (Brinkman et al., 2011). In the meso study by MacPhail et al. (2019) that evaluated a men’s participation program in South Africa, participants reported equality as a zero-sum game that meant respecting women equated to disrespecting men. In that intervention, activities included intensive small group workshops, informal community dialogue through home visits, mural painting to stimulate discussions of key messages, informal theatre, soccer tournaments, and film screenings. In another study, women’s oppression was maintained by men because they feared losing control of ‘their’ women (Devasia, 1998). In several studies, men shared their fear of being perceived as weak or feminine in front of their peers or community (Bigler et al., 2019; McCarthy & Moon, 2018; Murphy-Graham, 2009; Pierotti et al., 2018; Singhal & Rattine-Flaherty, 2006). Male participants in the study by Pierotti et al. (2018) believed that allowing women to be leaders in households would disintegrate society. They believed that upholding men’s lack of accountability and position as ‘boss’ was important to maintaining the fabric of society.

In contrast, Cislaghi (2018) found that men in Senegal did not resist increased political participation of women. And a radio program in Afghanistan that addressed gender equality was found not to offend men’s cultural or religious beliefs, and ultimately succeeded in changing attitudes and behaviours towards women and girls (Sengupta et al., 2007). The outcome included changes in the community, such as giving permission to women to leave their home alone, to vote, to go to school, and to reject child marriage. While participants expressed increased empowerment (micro), they also acknowledged that they may have their rights, but can never make decisions pertaining to their rights (Sengupta et al., 2007). For example, women may have the right to vote (macro), but they cannot go to vote or decide who to vote for without male guardianship (meso). In that study, 15 h of civic education material was promoted by radio, focusing on peace, democracy, and women’s rights. At the community level, interviews and focus groups with participants revealed that there was no resistance to listening to the radio program from men or families. However, the Sengupta et al. study was not longitudinal and had a relatively small sample of 115 people (72.2% women), and the women in the study may not have been in a position that allowed them to admonish the men in their community.

It was found in one study that resistance and backlash can be ameliorated by including men and boys in the development and delivery of interventions (Sengupta et al., 2007). Behaviour change in men required an increase in empathy to achieve the aim of gender equality (Becker & Swim, 2011). Hadjipavlou (2006) and Vachhani and Pullen (2019) found that empathy was a viable alternative feminist strategy. In their qualitative study, Hwang and Wu (2019) in Taiwan found that trust-building between civil servants and advocates reduced resistance and hostility. Activists in this intervention used four strategies: (1) Giving praise and encouragement instead of criticism and blame; (2) Engaging civil servants on a personal level to create bonding; (3) Appeasing fears about being blamed by offering assistance; (4) Attempting to invoke their identification with the values of gender mainstreaming through informal educational efforts, all of which are mesolevel strategies.

There was a wide array of types of change in different aspects of gender equality, with interventions varying in their success across settings and contexts. Table 2 summarises the types of change (e.g. legal, financial, behaviour, social) and the context (i.e., micro, meso, macro) that were identified and whether interventions aims were fully or partially achieved, or were not achieved, or had a harmful effect. Physical change, such as increased physical presence of women through inclusion or solidarity (meso) was the most consistently achieved beneficial outcome. Interventions targeting macrolevel social change, however, predominantly failed to achieve their aims or had harmful effects, reflecting how hard it is to realise social change, especially from a single, usually localised, intervention. Quotas could perhaps achieve their aim, although this finding was derived mostly from one good quality study (Johnson, 2019). The largest group of interventions were those implemented in education-based contexts, but these generally only partially achieved their aims, and focused mostly on physical changes (e.g., inclusion, solidarity). Most gender mainstreaming interventions did not achieved their aims.

Our broad inclusion criteria identified relevant interventions across a range of political, economic, social and cultural contexts, published over a thirty year period. Consistent with the recommendations by Garritty et al. (2021) we used rapid review methods; this may have led to the omission of some eligible studies. However, the use of a machine learning approach by reviewer two to rapidly screen a sample of the records predicted to be most relevant helped to limit the omission of relevant studies. Moreover, our restriction of literature to 1990 onwards may have omitted some studies conducted since the adoption of CEDAW in 1979. Given that only one study was published from 1990–2000, however, it is unlikely that this restricted timeframe had a significant impact on the review. Excluding papers not published in English is a limitation, and may have led to the omission of studies in some settings. We urge those who have non-peer-reviewed evaluations to submit them to peer-reviewed journals for future inclusion in reviews like the present one. The results of the large number of studies included in the review are difficult to generalise given the heterogenous study methods, intervention designs, populations, and settings. Because of a lack of reflexivity in most qualitative and multi-method studies, it is impossible to discern (for example) whether research undertaken in the Global South was conducted by Global North researchers. Moreover, there was no evidence of the ethical conduct of 16 studies and two studies did not have ethics approval. Together, these limitations may indicate potential problems with informed consent and implicit racial or other biases, although none were explicitly identifiable. There was insufficient evidence to assess whether and how culture played a part in attempts to achieve gender equality. Furthermore, while 86 percent of interventions predominantly or partially achieved their aims, this may inflate the effectiveness of such interventions because of reporting biases that favour publication of positive results (Sengupta et al., 2007; Sperandio, 2011).

This review has taken stock of successes and failures in seeking to promote gender equality. The findings reveal that undue reliance has been placed on the presumed efficacy of awareness raising, and that the race to achieve gender parity has not yet catalysed the desired social transformation. Entrepreneur programs can be exploitative, and legal actions have had limited effects, potentially failing because of men’s feelings about change. This review has shown that men can be fearful, resentful, jealous, and angry towards acts that disrupt the status quo. Until we adequately address these emotions and biases, the change that women (and potentially all genders) want, and the equality we all need will not be realised. Social context and systems thinking have shown us the importance of holism when tackling systemic discrimination. In this context, to be fully human is to be emotionally fulfilled. Ergo, human rights will be realised when there is dignity, humanity and positive emotionality among genders. Only then is the promise of CEDAW likely to be fulfilled.

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions. MJG was supported by an Australian Research Council Discovery Early Career Research Award (DE170100726). MG was supported by a Monash University Research Training Program stipend.